Where did you get the first idea for Wicked & Wise?

I was thinking about what I liked and disliked about cooperative games, and what kind of cooperative game I would design that would let me enjoy collaborating with another person. Normally, I don’t enjoy cooperative games because it is an open information puzzle that all players are expected to process at the same time. I, however, process that sort of puzzle much more slowly, and end up following the advice of the other players who have solved it. I could go through an entire game without having contributed to the victory or the loss.

The only exception to that would be cooperative games with limited information, restricted communication, or roles which were unique to my character, that only I could do. These restrictions helped give me the space to examine the puzzle at my pace, and getting the chance to contribute to the puzzle without everyone questioning my decisions or giving suggestions for strategies I hadn’t yet seen. They had to trust my decision.

I thought about how much I enjoyed playing Spades, which is a partnering trick-taking game, where you have to work together with a partner without knowing what’s in their hand. The independence of hidden information, but the appeal of collaborating with someone to be stronger motivated me to explore the idea further. So I decided to make a game where you are partnered, and each partner had a unique role. I wanted to put players in a position where they had to trust their partner’s decisions, but still needed to work together to reach a mutual goal. To me that embodies true cooperation.

What are some things you learned about playtesting during the Wicked and Wise development?

I learned that it’s very important to explain a trick-taking game as if all of your players have zero experience with the genre. It can be easy to slip into trick-taking terminology, because often people have grown up with it and the words feel commonplace, but it isn’t. Trick-taking is an intimidating genre because of that sense of either you grew up with it or you didn’t. It can isolate potential playtesters, so be mindful of that during the teach.

I also learned that because trick-taking is such an established genre it is an uphill battle when changing what is familiar, so make sure every change is purposeful and thought out. Even making up your own suits can be painful because you need to consider how people see the icons and make associations. You need to be able to look at card icons and almost immediately understand what suit that card belongs to. The regular 52 card deck is made of 4 distinct shapes: spades, clubs, hearts, and diamonds. You would never confuse one shape with the other. They also come in 2 colors, red and black. All of this helps us identify these cards in a split second and keep the game flowing, so when you make up new suits, they need to be just as easy to digest. You have to keep in mind that a diamond and a star are two pointy shapes that can be confused with one another at a glance, even though you know they are two unique shapes.

Another thing I learned was that establishing the game’s core was more important than ever when developing a game which attracts traditional and modern trick-takers. Each player came with a different set of expectations as to what makes up a good trick-taking game and why they enjoyed the genre. We also had players who didn’t enjoy trick-taking at all that we were also wanting to appeal to, because of the asymmetric twist added into the game. Balancing feedback from so many different perspectives meant the game got pulled in multiple directions. It was only because I was able to cement the identity and intent of this game with the Weird Giraffe development team that we were able to keep sight of what we wanted the game to be while implementing playtester feedback.

Did you learn anything about playtesting on TTS during the Wicked & Wise design and development process?

Playtesting in TTS was a boon for the most part, because it provided a way to develop the game when everyone was under quarantine. More than that, it allowed me to playtest a game which started out as 4-player only, on a consistent basis. Before TTS, I would’ve had to wait for conventions, and the occasional meetups, in order to get that many people to playtest the game. That being said, there were definite things that got obscured when testing digitally.

- Figuring out exactly how many coins were needed in a game, since infinite bags of coins don’t exist quite yet.

- Understanding how players would be seated, and how big text and icons needed to be so people could see across the table.

- What the ideal layout would be so everyone could see what was on the table without things getting too messy. It’s super easy to organize and label things in TTS, but when it’s just you and a blank table, things are different.

- How easy is it to hold 10 cards in TTS versus in your actual hands?

- How much easier or harder is it to peek at cards or communicate with a partner?

- How much time is lost or gained without the digital interface?

Overall, if you’ve done the majority of your development online, you want to scrutinize the user interface of your game and make sure the physical version is streamlined so that it’s as easy to play with as possible. Double check the sizes of everything, from fonts to components.

Wicked & Wise had three developers at one point! What did you learn about working with multiple people on the same project? Any tips on working with a number of people on a project?

I learned that each person has their own gaming style, same as with playtesters. This can be a boon and a complication. As a positive, that means you have people to help you consider every possibility of how the game might be played. I’m more feelings based in how I design, so I consider how players react and feel when playing the game. I am not as adept at considering the mathematics of a game, or balancing probabilities for a game someone might min max. So having a developer who deeply analyzes numbers is great, because they can help make sure the game addresses players who will strategize based on the numbers of the game.

The complication of working with people with different gaming styles is that we all find satisfaction in different aspects of the game. So development suggestions may be more biased in what we find enjoyable rather than in what stays true to the game’s core. I think that’s something to be considered regardless of what you work on. The biggest advice I can give is that you decide, as a group, what the game’s core is.

- Who do you expect to play it?

- How do you envision it being played in the ideal game?

- What kind of interactions should the players be having with one another?

Once you establish that, examine all suggestions under the light of whether or not it stays in line with what everyone agreed on. Discuss everything openly, whether you agree with something or not. It can birth new amazing ideas, or help coming to term with why a particular idea doesn’t work. Communication and openness is key to working with multiple people. Try to make sure everyone is on the same page, and that everyone is committed equally, time-wise. The good thing about working with others is that when you lack time, someone else can pick up the mantle. But you have to make sure it’s a balanced partnership. If too many people are short on time, it’s okay to say, hey let’s take a few weeks to let the project breath while we deal with life stuff, and then come back to it. Just be open and honest

What was the hardest part about working on an asymmetrical game?

The most difficult thing was making each role feel important while still creating the feeling that you’re on a team. I wanted to make sure that you could get invested in your role, but not so caught up that you didn’t care what your partner was doing.

In the first few iterations it often felt like two different games were being played that coincidentally had the same end goal. This feeling of teamwork was probably the most difficult thing to capture, because on top of the cognitive load of the roles, we also had to balance the level of communication between partners allowed. It took a while, but I’m really happy with our final solution.

What was the hardest part about working on a trick taking game?

I mentioned it earlier, but the most difficult part about working on a trick-taking game are the expectations people bring to the table. Trick-taking is one of the oldest game mechanics, so you’ll find a plethora of ways it has been implemented, and so, a variety of ways in which it is appreciated. I grew up with the deliciousness of the slow burn of Spades as you work for a come from behind victory making crazy bids to come out on top. The more modern trick-taking games, in comparison, are much shorter and snappier, and many come to expect that of any game in the genre. So expectations like these made it quite a challenge to make a game challenging the perceived norm. It also made us consider our playtesting feedback more carefully with that in mind.

What was something that you took out of the game that you didn’t really want to?

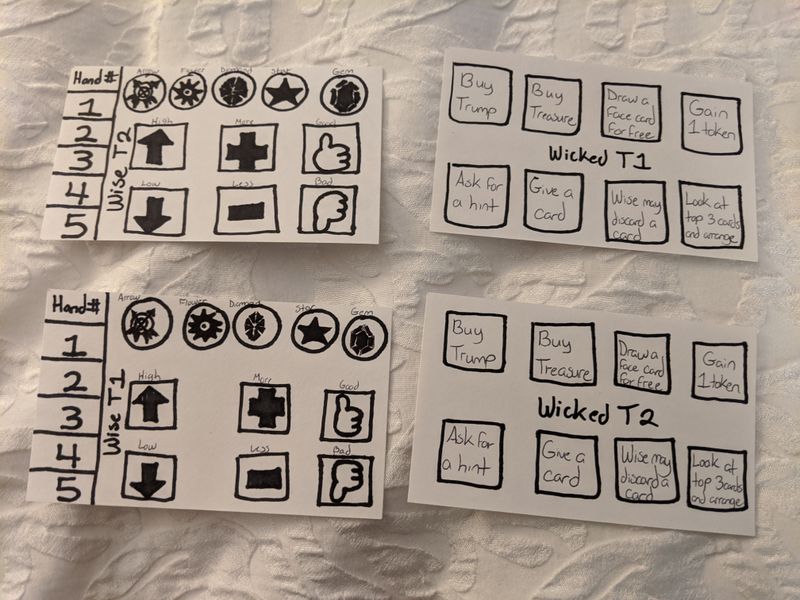

Way back in the earlier versions of the game, I had created player boards for the mice to share in order to take actions during each trick. I thought it was a really interesting mechanic, but ultimately, it didn’t feel quite right for Wicked & Wise. I still wonder what it would’ve looked like had it stayed in the game, but honestly I think it would’ve limited the mouse’s role, and messed with the flow of the game. The game absolutely became better without it. I do think it’s a nice mechanic to keep in my back pocket for a future game though.

What was the hardest part of the design or development process?

The hardest part of the development process was learning how to work with others before the full core of the game had been established. Wicked & Wise was signed very early on in its development process, before I had fully committed to its core. So once it was signed, I found myself suddenly in a new position where I had to communicate every idea I wanted to try and explain them when normally I would just do them and see if they worked out. I had to learn not to get defensive because my ideas were so raw and I had to share them before I felt “ready”. I didn’t have that barrier anymore.

I also had to deal with losing that sense of possession over a game much earlier than I had to for my first game. It was being developed and playtested without me being present in the earlier days, because the Weird Giraffe team had much more access to playtesters than I did, and could playtest nearly every week when I was lucky if I could playtest once in a month. It took alot of practice and communication to learn how we each worked best and how to get into our flow as a team, but once we did, it was the most gratifying experience I could ask for.

What was the best part of the design or development process?

The best part of the design process was enjoying the benefits of teamwork, and not having everything on my shoulders. It was still alot of work, but I got so much more energy because I wasn’t the only one banging my head against the wall trying to solve problems. The things I wasn’t good at, the others were. They could wrangle playtesters, and I could do the playtesting. I could concentrate on the parts I loved, and also, take solace that dependable people were taking care of the parts I didn’t.

Throughout the design process, what was the core of the game that you wanted Wicked & Wise to have?

I wanted a meaty partnering game where each partner had a special role, yet they had to trust their team mate and work together to win the game. I wanted it to be a game where people could trash talk or have hilarious table banter. I wanted a game that people who didn’t consider themselves gamers, but still enjoyed Spades or Euchre, would be able to play. I also wanted to reach out to people who didn’t normally play trick-takers and provide a role that let them play without the fear of playing the wrong thing and losing the trick.

What is your favorite part of game design?

Hands down, it’s playtesting. Sure I love coming up with an idea and seeing if it works, but really I’m in love with magic moments. When people play my games, and I’m lucky enough to see them have a magic moment, it’s the best feeling. To see them light up and banter with the other players, or to see them have a big dramatic play, it brings me back to my childhood and why I fell in love with games.

What are your favorite games to design?

I’m still too early in my journey to answer with confidence, but I’ll say that I really enjoy creating games to answer personal questions. What kind of game would I make if I could make any game is how I designed my first game, Book of VIllainy. What kind of cooperative game would I design that I would actually enjoy led me to Wicked & Wise. What kind of party game would make Mansplaining fun is how I co-designed Mansplaining. I enjoy seeing the final result of my answer to the questions.

How do you usually start designing games?

Usually I start by putting myself in the position of the consumer. If I saw or played a game about X, what would be fun about it? What would get me to play it?

What are you particularly good at as a game designer?

Maybe playtesting and iterating? I went to school for fine arts, so I’m used to public critique of my work and detaching myself from the moment. I mean of course I still feel like crap when I have a bad playtest, but I feel like I’m somewhat decent about not getting defensive when people are giving feedback. Usually I fully concentrate on writing down all the feedback given, and reserve reacting to the feedback to when I am alone and have the space to process everything.

Is there anything you’d like to improve on as a game designer?

There is a lot I’d like to improve, but for now I will say picking and choosing when to act on feedback. I listen to all feedback, and often explore whether it is helpful or not helpful to my game by implementing and testing it out. While I don’t think that’s horrible, I think it can waste a lot of time and confuse some of my design decisions because I didn’t filter it out beforehand. It goes back to establishing your game core and sticking to that when implementing design changes based on feedback. It’s not always easy to see what veers away from your core intent however, so I hope that’s a skill I will improve over time.

You can find Fertessa online

Did you enjoy this entry? What do you think would be the hardest part of the Wicked & Wise development process for you? Please let me know! I’d love to hear what you think and what kind of things you’d like to see from this blog. Feel free to send me an email or comment with your thoughts!

Don’t forget to sign up for my mailing list, so you don’t miss a post: https://tinyletter.com/carlakopp